Music videos have come a long way since the early days of MTV where labels and directors were feeling their way with the new format. Some were simple performance pieces against a plain background; some were culled from concert footage. Many of the successful early videos were almost like short films that followed the bands through a storyline.

These days videos are approached in much the same manner as fashion photography in that it's all about creating a unique look. And technically, they are much more complex with multiple locations and set builds, complex color treatment, editing and visual effects.

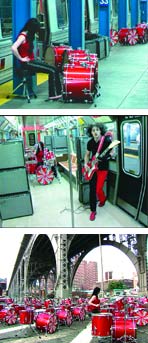

Lost Planet cut the The Hardest Button to Button, the latest video from The White Stripes, on an Avid.

|

VIDEO NATURE

There are several factors that make music videos unique in terms of production. First, the music video medium opens the door to an unlimited range of visual possibilities that include mixtures of performance, narrative and sometimes even abstract symbolic images, all of which may coincide with the song's theme or deviate completely from the song's tone and subject. Additionally, the three-minute format permits more latitude than a commercial and doesn't have to adhere to the strict structure of a feature film or TV show. So creatively, the door is wide open.

"The thing about music videos is every one is different. There's not a formula," explains Mark Intravartolo, Discreet Inferno artist at The Post Group (www.postgroup.com) in LA. "And the clients let you get more creative. With a commercial, the client tells you what needs to be done and you make it happen. With a music video you can say, 'Hey, I think this idea might be cool,' and 90 percent of the time you can get that shot into the video. They ask for your opinion more so you can make it more of your own."

While there is much creative freedom, the name of the game in the music video business is fast and furious. Once a record label decides to make a video, it expects that song to be on air within only a few weeks. This includes concept development, shooting, posting and approvals.

"The biggest challenge is the timeframe," says Bert Yukich, president of editorial/visual effects house of Kroma (www.kroma.biz). "You have less time to get more done."

Intravartolo adds, "People don't take the time doing music videos that they used to. There's a lot more pressure to get the videos done so they can capitalize on the radio play the song's getting… you just have to bang them out as fast as possible."

This fast track production pace is aided by the fact that the director is usually the one dominant voice, and the often-exhausting process of approvals and test screenings that prevail in commercials and films simply don't exist in the video industry.

"Things move along very quickly," notes Yukich. "There's a couple stages of approval: first the telecine, then the edit, which can vary a little, and then the beauty work. Artists will sometimes ask for more beauty work. The biggest thing is that the director has a lot of say in videos. The record company has final say but for the most part they leave it up to the director. It's not like commercials where there's a lot of chefs in the kitchen."

With little time, there is also relatively little money for music videos. "For most :30 commercials, the average budget is around $300,000," says Evan Schectman, president of NYC-based finishing house Outpost Digital (www.outpostdigital.com), which also has offices in Santa Monica and London. "For most music videos, even for A-list people, the budgets are basically the same, but the videos are several minutes long."

COLOR

The biggest difference between the post production of music videos and commercials or films is that the telecine transfer is generally the first step after production is wrapped and the footage is processed. This is where the stylized color is established.

"The normal telecine process on a video is they come up with five or six different looks and you transfer all the footage in those five or six looks, which are all approved by the record label," explains Gareth O'Neil, president of production/post company Reconnaissance Films (wwww.reconfilms.com) in LA. "That way everybody has agreed what that look is going to be, and once they do their edit they've got locked picture."

Editor Paul Martinez of editorial house Lost Planet (www.lostplanet.com), which has offices in New York and Santa Monica, predominantly cuts commercials and notes that when cutting videos, "it's great to work with the final color corrected film. Everyone knows what it's going to look like in the end so you don't have to manage expectations." With commercial clients he has to explain that things will look different with the color in place.

Outpost Digital recently completed music video work for (from L-R) Pink, Korn and Thalia. Final Cut Pro and Shake were the favored creative tools.

|

While doing the telecine transfers first is the standard practice with music videos, there are always exceptions to the rule and some projects might get color correction after the edit is locked. This happened with the video for the song "No Fucking Around" by The Special Goodness. "For this video, we transferred everything with a really good best-light because our texturing process happens in the Inferno," explains O'Neil. "That's where we like to like to peel things apart and do our color correction as opposed to trying to predict what's going to happen with the edit. I feel we can work more organically that way. Then we'll go back and transfer selects to maximize what can be done in the telecine."

Even when the telecine transfer is done up front though, the footage is again heavily processed with secondary and tertiary color correction and effects in the finishing system. "It's rare that we'll run an image by itself clean," relates O'Neil. "Sometimes it's an obvious effect; sometimes it's very subtle where we desaturate and blur it to add a little texture to the low lights. Thanks to the Sparks we use - the Sapphire plug-ins - we play around with the parameters. It's a little unpredictable but when it works we come up with a look that no one else has."

Editorial/design/effects house MK12 (www.mk12.com) in Kansas City, which usually works solely on commercials and broadcast design, recently finished its second music video, which was conceived, produced and posted via production company The Ebeling Group. The video for the band Hot Hot Heat's song "No, Not Now" plays out like a comic-book-style, action-adventure story through an other-worldly amusement park complete with a sexy heroine suited up in vinyl and evil villains in bunny suits. The video was filmed at the MK12 soundstage against greenscreen using a combination of stationary (Panasonic 24p DVX100) and hand-held cameras. Design work was completed in Illustrator and Photoshop, and was keyed using the Ultiimatte Primatte and Advantage plug-ins for After Effects. The sequences were assembled in After Effects and timings were tweaked using Final Cut.

|

THE EDIT

While there is a general structure laid out in the director's treatment, in large part the editor develops the structure, balancing the performance footage with any B-roll or story footage. "When there is performance footage and a story, the trick is making them both work, so the performance doesn't throw you out of the story and the story doesn't distract you from the performance," explains Lost Planet's Martinez.

Martinez, who is based in Santa Monica, first screens all the footage and marks the best performance clips. "Then I stack all the performances on top of each other [in the NLE] all synced so I can go back and forth between them easily," he explains. "Then on the lyric sheet I'll write the timecode for every line so I can use a performance from the second chorus in the first and shift things around depending on the performance. I do a performance-only edit and then go back and integrate the story. A lot of times when you try to integrate the story you find you're wiping out a great performance and you have to shift things around. Even when there is a story, I'm asked to cut a performance-only version so the label and the artists can see it compared with the cut that integrates the performance and the B-roll. Sometimes performance-only cuts work best."

Other than being somewhat limited by maintaining sync between the performance and music, the possibilities are endless when editing videos, a prospect that makes commercial editor Martinez want to continue editing videos, even if the jobs are not as lucrative as commercials.

"You have a lot more creative freedom cutting a music video," he says. "You can cut in a linear way or make it completely abstract. You're not locked into dialogue, voiceover, anything, so it's fun trying to give the viewers something that adds to the song, especially when it's a good song."

For this recent video from The Special Goodness, Reconnaissance Films used Inferno to tileDV footage together.

|

EFFECTIVELY BEAUTIFUL

Of course, the record labels' main purpose is to sell the music and create an image for the band. The desired image of today is one of beauty and riches, and great efforts are taken to project this. So while the effects in some videos rival the effects of films and commercials, the majority of the effects work is aimed at making beautiful people more beautiful.

"Even with a straight online, no effects, you're guaranteed a lot of clean-up beauty work," reports Kroma's Yukich, who uses the Avid|DS. "Removing sweat, freckles, wrinkles on the men and the women. No one has wrinkles now."

But this beauty work doesn't stop with the removal of imperfections; it's about creating perfection. "Most of the effects are giving women six-pack abs, fixing their eyes, giving them bigger boobs," relates The Post Group's Intravartolo. "I spent a week of my time recently doing double-chin removal on one artist. A lot of artists are only concerned with looking good, and the Inferno's still cheaper than plastic surgery."

MOVIE TIE-INS

Videos get significantly more complicated when they need to promote the band as well as a newly-released feature film.

For the video of Ricky Martin's Juramento, Kroma replicated 50 Ricky Martins dancing in the desert. They textured the 3D CG head of Martin in Softimage|XSI.

|

"The challenge technically is to aesthetically get the footage of a music video to match the tone of the picture," explains Reconnaissance's O'Neil. "Also, the studio's involved, and they might want to vary their marketing. The film might be a comedy, but they want to skew their marketing to drama. So we have to give the footage the tone to match that subtext."

Along with the challenge of seamlessly integrating the film's footage into the video, the usual quick and painless approval process becomes longer and more complex.

"The editor will cut it, then it has to get approval from the director of the feature and the studio, because they don't want the movie to be reflected in a bad way. Then there's the record label and the video director, the artist, the lawyers... so there are a lot of hands touching it," explains Intravartolo. Still, it all comes back to the tight time schedule "You have to do it quickly because the movie's going to theaters and they want to saturate the market."

SETTING UP FOR VIDEOS

Outpost was building out its Santa Monica office just over a year ago at the same time its parent company @Radical Media was launching its music video production division, so Outpost tailored its studio to handle the specific needs of this workload.

"We put together Shake artists, good, quick online editors, people who know secondary color correction, then the right technical backbone," explains Schectman. "And we set up our own private T-1 network for realtime video conferencing and playdown so we can send near broadcast-quality video at 30fps back and forth from New York and LA for approval."

Outpost also set up its studio with the price structure of videos in mind. "We're using systems like Final Cut Pro and Shake, and less big systems like Flame and Inferno, though they [music video producers and post supervisors] still rely heavily on those systems because they don't have the time," notes Schectman. "But with the crop of artists coming up now, they can run these systems just as fast as a sophisticated operator on a bigger system. That's been a big selling point because we've been able to change the cost structure for post without slowing it down."

FOR THE LOVE OF VIDEOS

The fast and furious schedule, the proliferation of videos centered on scantily-clad dancing girls and the narcissistic push to enhance the beauty of the artists at times makes some post pros weary of music video work, but it's these projects that allow them to push the creative envelope.

Modern Video Productions (www.modernvideoproductions.com) in Philadelphia recently provided pre-mastering and online services for a music video DVD that combines the rock music of CKY with footage of skateboarder/MTV Jackass star Bam Margera. Infiltrate Destroy Rebuild was onlined on Modern Video's Avid 9000 XL by editor Pete Mecchi. Sister studio Modern Audio expanded the 10 stereo cuts and two bonus tracks into Dolby Digital remixes for the DVD using Dolby's 562 encoder and 569 decoder. Michael Nutt handled the DVD authoring.

|

"There are some amazing videos out there and people are doing groundbreaking work," says Martinez. "Music videos are really a labor of love. The money's not even in the ballpark of the money in commercials. In a way though, that makes it better because you're not always worried about how much money you're spending and it makes it more of a creative outlet."

O'Neil says there are two types of videos: the ones that are a job and the ones that you love, like the video they're working on called No Fucking Around. O'Neil loved the song and called the band's management to ask if they could do a video.

It's projects like this that keeps O'Neil excited about creating music videos, explaining, "Here [at Reconnaissance Films] we like to have a sense of ownership in the projects we do, and music videos allow you to do that."